Many people seem to regard harmony and peace as fundamental values, especially in their relationships. And sometimes cultures endorse a particularly low-conflict or conflict-averse interaction. Yet, it is precisely the argument, the conflict, and possibly even the tangible dispute that enables us to grow and feel as “we” ourselves.

Now that doesn’t mean we have to fight incessantly. It does mean that conflicts, where they arise, have to be discussed to develop further. In the friction and confrontation with other people, we learn something about the other and ourselves.

Total conflict avoidance often results from fear and often does more harm than good to relationships. Gestalt therapy knows the defence mechanism as confluence. The word comes from the Latin word confluere, which means “to flow together”.

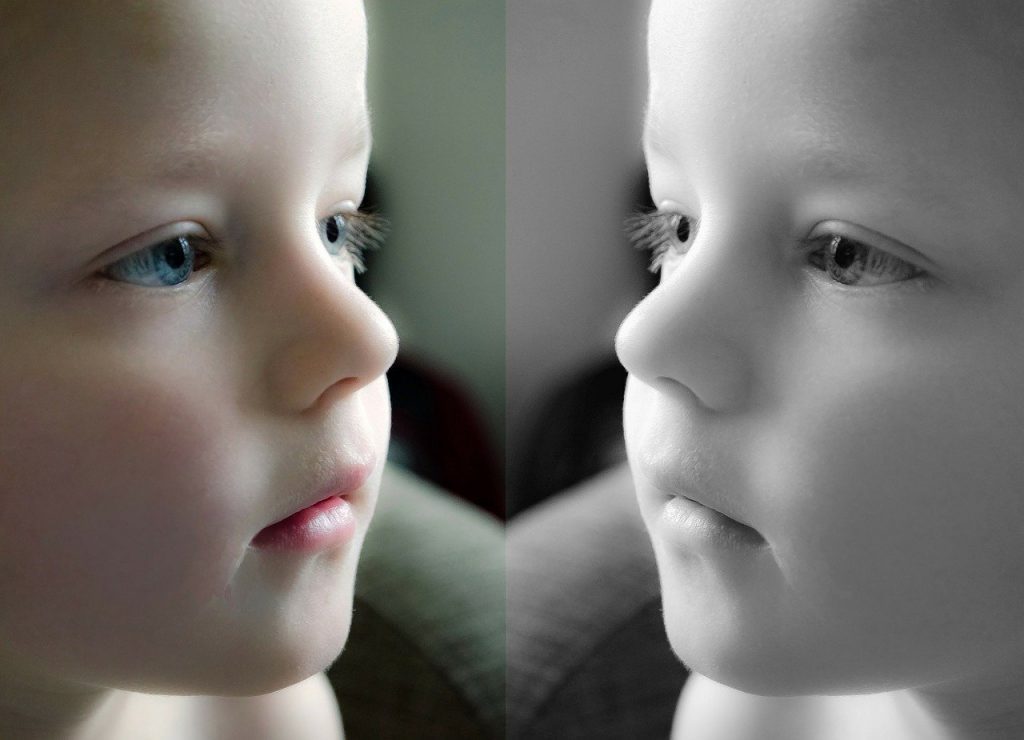

Confluence is the term used to describe the process of flowing into one another between two or more people. There is a loss of perception or denial of differences between people. The typical consequence of this is that they no longer disagree. Creative conflict, or simply good contact, is abandoned for routine interactions that are flat, static, and secure (Zinker, 1982) in the name of some prescient knowledge of “what the other wants”.

If we are confluent with other people, we lack the contact surface to our environment. The difference between subject and object is either blurry or ignored. A typical example would be the following sentence from a woman to her husband: “I know, papa, we both like to eat goulash.” The wife pretends that there are no differences between her and her husband and negates any differences.

Strictly speaking, confluence already begins where we think we know with complete certainty what makes our partner tick, what he thinks and what he likes. And in many couple relationships, there has not been a personal conversation for years, in such a way that we exchange ideas about what we think, what we feel and what we want. Dialogues are often only about everyday things, what is on TV in the evening, who takes down the garbage and who takes the children to kindergarten.

Linguistically, the frequent use of the words “one” and “we” tells us that a person is little awareness of their own identity and has a lack of sense of where her self ends and where others begin.

In particular, those who constantly orient themselves towards other people’s expectations and avoid any conflict are called confluent. That also includes the need for harmony and closeness at all costs. Aggression as a contact function is then either underdeveloped or does not exist at all. Conflicts are avoided to secure being in harmony with the environment.

Incidentally, a particular form of confluence is the “opposition for the sake of opposition”. There is no clear boundary, but the person concerned acts in rigid dependence on the environment, without really feeling her own needs and desires: “When my wife says A, I say B, but I don’t know what my opinion really is.” That is not genuine autonomy, but instead dependency with a negative sign.

In therapy, confluence may appear in the attempt to seduce the therapist into one’s point of view. “You believe that …”, “I am sure you also believe that …”, “You probably think I am a failure too!” Or “I am the most stressful client for you!” etc.

(Due to the particularly protected atmosphere of a therapy situation and the possibility of getting to know a person more deeply than usual in everyday life, therapists are sometimes at risk of becoming confluent with clients. That is particularly evident in the tendency to agree with the client too quickly, be very careful with specific clients, or regularly overdo the hours with particularly sympathetic clients. Supervision is necessary here to reflect on this behaviour, mainly because a confluent therapist with the client cannot be helpful.)

Confluence initially fulfils a vital function, namely togetherness, and enables cohesion in groups or the family. We speak of a contact disorder only when confluence becomes the exclusive or predominant pattern in encountering others.

In general, confluence offers only a weak basis for a relationship. After all, people cannot always be of precisely the same opinion. As such, confluence is often involved, especially in particularly harmonious relationships. Yet, such a relationship is dead inside. There is no longer any exchange and no actual contact. There are no more conflicts to provide a feeling of security and agreement.

The cause or root of very confluent relationships is often insecurity or sometimes a deep grudge. If one of the two partners then violates confluence, he feels guilty, and the other feels “righteous anger”. After all, he has been sinned against. However, it is precisely the handling of conflicts that offers an opportunity to break through the confluence and get to know each other anew and more deeply than before.

On the other hand, there are also confluence contracts with society. People focus on a behaviour that they consider socially desirable. They might not be in contact with themselves or with others. Such a person never asks herself what she wants and needs but always behaves as she thinks that is expected of her.

According to Solomon Friedlaender, the appropriate adult behaviour lies in the middle between the extremes (also called the zero point or the point of indifference). That would be the ability, on the one hand, to delimit and assert oneself appropriately and, on the other hand, to adapt.

The antidotes to confluence are contact, differentiation, and articulation (Polster, 2001). Questions like: “What am I feeling right now?”, “What do I want right now” and “What am I doing right now” can help re-establish contact with ourselves. Such questions strengthen one’s ego boundaries, a feeling for who we are, what we need and where the needs of others begin.

As infants, we use confluence to avoid the horror that arises when we become aware that we are separate from others. The couple relationship and especially the sexual act give us the feeling that we are one, even if only for a short time. But this oneness is an illusion.

Relationship as a merging fantasy is a childlike variant of fear avoidance. As adults, we are all different. A relationship does not consist of becoming one with another, but also in the conflict and tension between people who rub against each other.

Only by addressing our own needs and articulating them do we get to know ourselves and the other. Even if the partner says “No”, I have the chance to learn something new about myself, and in the constant argument, I also realise that the partner I meet today is different from the one I met yesterday.

***

Polster, Erving und Miriam (2001): Gestalttherapie. Theorie und Praxis der integrativen Gestalttherapie. Peter Hammer Verlag.

Zinker, Joseph (1982): Gestalttherapie als kreativer Prozess. Junfermann Verlag.