Strategies for overcoming toxic shame

- Strategies for overcoming toxic shame

- Introduction to toxic shame

- Foundations for a healthy identity and self-esteem

- Cognitive skills and emotion regulation

- Identity and individuation development

- Work on yourself

- Therapeutic strategies and techniques

- Psychodynamic strategies

- Cognitive-behavioural therapeutic strategies

- Schema therapy strategies

- Self-forgiveness and self-acceptance

- Self-help strategists

- Practical application and exercises

- Conclusion

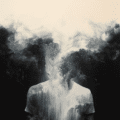

Introduction to toxic shame

Toxic shame is a profound emotional experience that harms self-image. It goes beyond simple shame and leads to long-term psychological problems.

Foundations for a healthy identity and self-esteem

Overcoming this involves developing a holistic view of oneself and a healthy sense of self-worth. Several prerequisites are essential for their development.

Cognitive skills and emotion regulation

Developing a healthy identity and stable self-esteem requires good cognitive knowledge and the ability to regulate emotions. These skills enable better understanding and processing of complex emotions such as shame and guilt.

Emotion regulation strategies for dealing with shame and guilt include recognising and processing these emotions, understanding their triggers and developing coping mechanisms such as self-compassion, self-care and emotional self-efficacy.

Such skills can be acquired, for example, with mindfulness-based self-help techniques or in therapy, which help to understand oneself better, explore feelings and scrutinise self-critical thoughts. This process also makes it possible to reconcile an idealised self-image with the authentic self and thus overcome self-doubt and self-devaluation.

Identity and individuation development

Building on this, the promotion of identity and individuation development is crucial. It helps those affected to recognise and appreciate their uniqueness. This results in self-confidence and a more robust inner anchor.

Self-confidence helps build a positive self-image and learn to appreciate one’s values and needs. That creates a deeper connection to oneself with a better sense of self-worth and a stronger identity.

Work on yourself

Work on yourself and a healthy lifestyle to support people who struggle with feelings of shame and guilt in various ways. They strengthen a positive self-concept, self-esteem and a sense of personal control. A healthy diet, exercise or meditation contribute to a sense of well-being and emotional resilience. That enables those affected to bounce back after an experience of shame. They are also a form of self-care and self-compassion.

Therapeutic strategies and techniques

Therapy encourages individuals to explore and accept their authentic selves, imperfections and weaknesses by providing a safe and supportive environment for self-exploration and growth. Therapeutic strategies for overcoming toxic shame are particularly effective when it comes to working with emotions and accepting aspects of oneself that were previously denied or suppressed. Therapy strengthens self-awareness, self-acceptance, and self-compassion and creates an inner place of self-evaluation free from self-judgement. Those who can accept shortcomings and weaknesses do not have to judge themselves for mistakes and gain a compassionate and understanding relationship with themselves and others without losing their ability to criticise themselves or others.

As mentioned above, idealised self-images are explored, and their origins are uncovered, often rooted in societal expectations, personal experiences or childhood dynamics. Such exploration helps individuals to recognise and challenge distorted beliefs about themselves to develop a more realistic and authentic self-concept.

Therapy or counselling achieves this by creating a safe space where shame can be confronted, felt, accepted and expressed. Therapists support people in processing and coping with complex emotions related to shame and in forgiving themselves or others. It challenges self-defeating beliefs, normalises and corrects, and focuses on a hopeful and meaningful future perspective.

Psychodynamic strategies

In psychodynamic theory, especially in more recent developments, various fundamental conflicts that describe profound inner tensions and developmental problems are identified.

- autonomy vs. dependency,

- submission vs. control,

- need for care vs. autarky,

- self-worth conflicts,

- guilt conflicts,

- sexual conflicts, and

- identity conflicts.

All basic conflicts deal with central inner-psychological tensions. Conflicts such as dependency versus autonomy, self-worth versus object value and egoistic versus prosocial tendencies of guilt conflicts are closely linked to feelings of shame.

- autonomy vs. dependency

This conflict describes the tension between the desire for attachment and relationships and the striving for independence and autonomy. The causes may lie in early childhood, such as how attachment experiences with primary caregivers were organised.

- self-worth conflicts

These conflicts centre on the regulation of self-esteem, which is influenced by external recognition (object value). The causes can often be found in experiences of judgement by others, particularly in childhood.

- guilt conflicts

These conflicts address the balance between selfish needs and the need to help others or to behave in a socially desirable way. The causes can lie in family and social conditioning, where values and norms are conveyed.

This strategy aims to help patients understand and work through these inner conflicts to overcome their toxic shame. That is done by analysing early experiences, becoming aware of unconscious conflicts and working on developing a more realistic and benevolent self-image.

The procedure is based on psychoanalysis and includes techniques such as clarification, confrontation and interpretation.

- autonomy vs. dependency

Through clarification, the therapist can help the patient recognise the tension between the desire for closeness and the need for independence. Through confrontation, the therapist could challenge the patient to consider situations in which shame results from the fear of rejection when autonomy efforts are displayed. The interpretation would then be used to understand how early attachment experiences and fear of rejection shape the current conflict situation.

- self-worth conflicts

In clarification, the therapist works with the patient to identify the causes of fluctuating self-esteem heavily dependent on external validation. Confrontation can be used to confront the patient with the reality of their self-perception and dependence on the approval of others. Interpretation provides insight into the deeper unconscious reasons for needing external validation and how this relates to past experiences.

- guilt conflicts

As part of the clarification process, the therapist could help the patient reflect on their behaviour in social situations, especially when feelings of shame arise when their needs are seen as selfish. Confrontation can be used to directly confront the patient with the conflict between their own needs and the desire to help others. Interpretation then helps to understand the unconscious motives behind these tendencies and how they are linked to toxic feelings of shame.

This application of the techniques enables a deeper exploration and processing of the conflicts that lead to toxic shame and supports the healing process.

Cognitive-behavioural therapeutic strategies

CBT challenges dysfunctional thought patterns and replaces them with healthier ones. Toxic shame is about questioning self-critical thoughts and developing coping strategies for emotional self-efficacy.

This strategy overcomes shame and guilt by testing, examining and correcting self-harming assumptions, thoughts and beliefs. That also reduces the intensity of shame and, under shaming, allows feelings of guilt to be uncovered. It may sound surprising, but this shift can lead to emotional resilience when guilt related to a specific behaviour rather than the whole self allows one to take responsibility for action and seek to make amends rather than drown in feelings of inadequacy and self-condemnation.

Cognitive behavioural techniques also include assertiveness training, which allows irrational thoughts that contribute to feelings of shame to be recognised and combated. In particular, it helps those affected to assert themselves in the face of external condemnation or shaming, draw boundaries, and reject offensive behaviour or statements that fuel feelings of shame.

To do this, CBT applies techniques such as reflective and Socratic questions to experiences that have triggered feelings of shame. She reviews them to question automatic thoughts.

For example, Socratic questioning can be used to scrutinise the reality of shame-related beliefs in the case of toxic shame. An example could be: “What proves that I am inadequate?” That encourages critical reflection and helps to evaluate the validity of negative self-judgements.

Reflective techniques mirror how feelings of shame distort self-perception and encourage thinking about alternative, more positive interpretations of experiences. By recognising and challenging negative thoughts, sufferers can gain insight into their cognitive distortions and develop a more realistic and adaptive perspective on their experiences, ultimately facilitating the process of self-forgiveness.

Finally, reframing helps those affected reinterpret situations in a more positive and self-compassionate light. By shifting from shame to acceptance of responsibility, individuals can learn from their mistakes and achieve self-forgiveness.

Schema therapy strategies

Jeffrey Young’s schema therapy identifies 19 schemas and various modes that can be relevant in overcoming toxic shame. These schemas can lead to persistent emotional difficulties and dysfunctional relationships. Schema therapy, therefore, aims to create awareness of these beliefs, develop strategies to overcome them and promote healthier behaviours and thoughts.

Self-centred core beliefs, such as “inadequacy/shame”, “self-sacrifice”, and “striving for approval”, activate deep-seated patterns of perception and feeling that stem from early life experiences. They address central emotional patterns that influence self-image and interpersonal relationships:

Inadequacy/shame refers to deep-rooted feelings of inferiority and shame. Those affected are convinced that they are inadequate or flawed in fundamental aspects.

Self-sacrifice is characterised by an excessive tendency to put the needs of others above one’s own, regularly at the expense of one’s well-being.

Striving for recognition is characterised by a strong need for recognition and admiration from others, often combined with a fear of rejection or criticism.

“Mode”, on the other hand, refers to a momentary emotional state or behaviour that is activated by certain fundamental beliefs in a situation. Modes represent the way someone feels and acts in certain situations based on their schemata. Only by working with modes is it possible to recognise and change unconscious dysfunctional emotional patterns to promote healthier coping.

There are different modes, such as the ‘vulnerable child mode’, which involves deep-seated feelings of fear or shame, and the ‘critical parent mode’, which requires self-criticism and harsh judgements about oneself. They represent states or roles an individual assumes in response to certain situations.

Finally, schema therapy distinguishes between three main categories of coping mechanisms: avoidance, overcompensation and acquiescence. That is how those affected try to deal with painful schemas, often in a way that is not helpful in the long term.

Schema therapy offers a range of techniques for dealing with these schemas and modes, including

Logical review: The aim is to challenge and change disruptive thought patterns.

Behavioural experiments: Trying out new behaviours in the real world helps to activate emotions, confront them, overcome them and gain corrective experience.

Imaginative techniques: Imaginations make it possible to process and reinterpret painful memories in a protected way.

“The empty chair” uncovers inner conflicts and allows them to be dealt with by “dialoguing” different aspects of the self or the self and essential attachment figures.

These techniques help to overcome dysfunctional coping mechanisms associated with toxic shame and promote healthier self-perceptions and behaviours.

Self-forgiveness and self-acceptance

Therapeutic programmes for overcoming toxic shame offer a safe space to explore and accept shame without judgment. They emphasise the importance of self-acceptance and encourage active engagement with one’s emotions and beliefs.

They help people explore and accept their authentic selves, imperfections and weaknesses through techniques that focus on confronting, feeling, accepting and expressing shame and other accompanying emotions. By discussing and processing these problematic and isolating experiences in therapy, individuals can gradually come to terms with their true selves and build a more authentic and accepting relationship with themselves.

All therapeutic approaches, therefore, seek to facilitate greater self-awareness and self-acceptance by focusing on the individual’s inner experiences, emotions and beliefs. They emphasise the importance of acknowledging and accepting one’s feelings, challenging negative self-beliefs and promoting personal growth through self-improvement and reframing techniques. Overcoming toxic shame involves exploring one’s values, beliefs and choices and learning to take control of one’s feelings, thoughts and behaviours.

Self-compassion practices are central to dealing with feelings of shame and guilt. Techniques such as self-compassion and self-care promote emotional healing and contribute to developing a positive self-image.

Therapy can help to increase an individual’s self-awareness, self-acceptance and self-compassion by creating a safe and supportive environment in which the individual can explore their emotions, vulnerability and self-awareness.

Strategies to overcome toxic shame, therefore, empower individuals to take control of their emotions and promote a more authentic sense of self. By actively dealing with their feelings and experiences, those affected gain a greater understanding of autonomy, self-confidence and an integrated self-image.

People can learn to be more compassionate towards themselves through techniques such as self-forgiveness, self-affirmation and reframing negative self-beliefs. By seeking more profound meaning, understanding and self-transcendence, individuals can develop a more positive and accepting relationship with themselves, ultimately reducing self-judgement and fostering a compassionate connection with themselves and others.

Self-help strategists

The strategies described so far have revealed several effective coping mechanisms for dealing with feelings of shame and guilt:

– Confrontation, acceptance and expression of shame and the emotions that accompany it

– Questioning negative judgements and self-defeating beliefs

– Differentiation from the abusive behaviour of others or toxic environments

– Self-compassion, self-forgiveness and self-acceptance

In particular, the promotion of self-acceptance through identity and individuation development contributes to building a positive self-image and strengthening one’s sense of identity and self-esteem:

– She encourages those affected to explore and accept themselves, including all their imperfections and weaknesses.

– It promotes self-forgiveness, self-compassion and self-affirmation to counteract shame and guilt.

– It supports those affected in developing a more internal evaluation standard, in which their own opinion counts more than external judgements.

– It encourages you to search for a deeper meaning and build a stronger connection to your core values and beliefs.

Mentalisation plays an essential role in this context. It is the ability to understand and interpret one’s own and other people’s mental states. That includes emotions, needs, desires and beliefs. In the context of overcoming toxic shame, mentalisation helps to put one’s shame-related feelings and thoughts into a meaningful context and to understand their origins. By strengthening the ability to mentalise, it becomes possible to recognise self-harming beliefs and behaviours, talk about them with others and change them. That paves the way to self-acceptance and emotional health.

Self-awareness, mentalisation and self-compassion play an essential role in regulating emotions, challenging self-defeating beliefs and developing self-acceptance on the path to self-forgiveness. Mindfulness practices such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) aim to create the opportunity to be present in the moment, to acknowledge and accept thoughts and feelings without judgement, and to cultivate a sense of self-compassion and kindness towards oneself. Self-compassion involves creating a kind and affirming inner dialogue, recognising the value of refocusing on compassion motivation, activating the compassion system and practising self-compassion to address areas of distress.

Practical application and exercises

The following exercises help you to work on self-forgiveness, self-affirmation and the transformation of negative self-beliefs:

Self-forgiveness

Write a letter to yourself in which you reflect on situations in which you cannot forgive yourself. Acknowledge your feelings and write why you forgive yourself and how to move forward.

Self-affirmation

Start each day with positive affirmations. Choose statements that emphasise your values and strengths, such as “I am valuable” or “I have the strength to overcome my challenges”.

Reshaping negative self-beliefs

Identify a negative belief about yourself. Critically scrutinise it and replace it with a positive, more realistic statement. Practise regularly to internalise this new belief.

The following practical exercises aim to replace self-critical thoughts with self-compassionate affirmations.

Diary exercise

Start by keeping a daily diary in which you write down your thoughts and feelings. Pay particular attention to moments when you feel self-critical. Write down what happened, how you felt and what thoughts went through your head. Review your entries at the end of the week to recognise patterns of self-critical thoughts and question how realistic they are.

Mindfulness practice

Take a few minutes every day to do a mindfulness exercise. Sit or lie down comfortably and concentrate on your breathing. Observe your thoughts and feelings without judging them. If your attention wanders, gently direct it back to your breath. This exercise helps you to stay in the moment and accept your feelings without judgment.

Self-compassion meditation

For this exercise, sit in a comfortable position and close your eyes. Imagine a situation in which you have felt self-critical. Now imagine how you would respond to a good friend with the same problem. What words of encouragement and compassion would you say to them? Now, try to apply these words to yourself to strengthen your self-compassion.

Conclusion

In this comprehensive guide, strategies, practical exercises, therapeutic approaches and perspectives on overcoming toxic shame were presented to show those affected how to achieve a healthier self-image. Strategies such as self-forgiveness, self-affirmation and reshaping negative self-beliefs took centre stage. By integrating these strategies into everyday life, those affected pave the way to more profound self-acceptance and a more fulfilling life.

This process requires a comprehensive understanding of the underlying psychodynamic conflicts and the use of specific techniques for self-reflection and self-acceptance, backed up by commitment and therapeutic support.

Dealing with toxic shame requires a comprehensive understanding of the underlying psychodynamic conflicts and the use of specific techniques for self-reflection and self-acceptance. The exercises and approaches presented offer valuable tools for recognising and positively changing individual patterns.

Literature:

Ashley, Patti. 2020. Shame-Informed Therapy: Treatment Strategies to Overcome Core Shame and Reconstruct the Authentic Self. Eau Claire, Wisconsin: Pesi Publishing & Media.

Austin, Sue. 2016. “Working with chronic and relentless self‐hatred, self‐harm and existential shame: a clinical study and reflections.” Journal of Analytical Psychology 61 (1): 24–43.

Bach, Bo, and Joan M. Farrell. 2018. “Schemas and modes in borderline personality disorder: The mistrustful, shameful, angry, impulsive, and unhappy child.” Psychiatry Research 259 323–29.

Boddice, Rob. 2019. A History of Feelings. London: Reaktion Books.

Brown, Brené. 2006. “Shame resilience theory: A grounded theory study on women and shame.” Families in Society 87 (1): 43–52.

Clark, Timothy R. “The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety.”

Collins, George N., and Andrew Adleman. 2011. Breaking the Cycle: Free Yourself From Sex Addiction, Porn Obsession, and Shame. New Harbinger Publications.

De Paola, Heitor. 2001. “Envy, jealousy and shame.” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 82 381–84.

DeYoung, Patricia A. 2021. Understanding and Treating Chronic Shame: Healing Right Brain Relational Trauma. New York: Routledge.

English, Fanita. 1975. “Shame and social control.” Transactional Analysis Journal 5 (1): 24–28.

Erskine, Richard G., Barbara Clark, Kenneth R. Evans, Carl Goldberg, Hanna Hyams, Samuel James, and Marye O’Reilly-Knapp. 1994. “The dynamics of shame: A roundtable discussion.” Transactional Analysis Journal 24 (2): 80–85.

Frost, Ulrike, Micha Strack, Klaus-Thomas Kronmüller, Annette Stefini, Hildegard Horn, Klaus Winkelmann, Hinrich Bents, Ursula Rutz, and Günter Reich. 2014. “Scham und Familienbeziehungen bei Bulimie. Mediationsanalyse zu Essstörungssymptomen und psychischer Belastung.” Psychotherapeut 59 (1): 38–45.

Greenberg, Tamara McClintock. 2022. The Complex Ptsd Coping Skills Workbook: An Evidence-Based Approach to Manage Fear and Anger, Build Confidence, and Reclaim Your Identity. New Harbinger Publications.

Heller, Laurence, and Aline LaPierre. 2012. Healing Developmental Trauma: How Early Trauma Affects Self-Regulation, Self-Image, and the Capacity for Relationship. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books.

Hirsch, Mathias. 2008. “Scham und Schuld – Sein und Tun.” Psychotherapeut 53 (3): 177–84.

Klein, Melanie. 1984. Love, Guilt, and Reparation, and Other Works, 1921-1945. New York: The Free Press.

Konstam, Varda, Miriam Chernoff, and Sara Deveney. 2001. “Toward forgiveness: The role of shame, guilt anger, and empathy.” Counseling and Values 46 26–39.

Lammers, Maren. 2020. Scham und Schuld – Behandlungsmodule für den Therapiealltag. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

MacKenzie, Jackson. 2019. Whole Again: Healing Your Heart and Rediscovering Your True Self After Toxic Relationships and Emotional Abuse. Penguin.

Mayer, Claude-Hélène, and Elisabeth Vanderheiden. 2019. The Bright Side of Shame: Transforming and Growing Through Practical Applications in Cultural Contexts. Cham: Springer Nature.

Miller, Susan. 2013. Shame in Context. Routledge.

Morrison, Andrew P. 1983. “Shame, Ideal Self, and Narcissism.” Contemporary Psychoanalysis 19 (2): 295–318.

Rafaeli, Eshkol, Jeffrey E. Young, and David P. Bernstein. 2013. Schematherapie. Junfermann Verlag GmbH.

Roediger, Eckhard. 2016. Schematherapie: Grundlagen, Modell Und Praxis. Stuttgart: Schattauer.

Saenz, Victor. 2018. “Shame and Honor: Aristotle’s Thymos as a Basic Desire.” Apeiron 51 (1): 73–95.

Scheff, Thomas J. 2000. “Shame and the social bond: A sociological theory.” Sociological Theory 18 (1): 84–99.

Scheff, Thomas J. 2003. “Shame in self and society.” Symbolic interaction 26 (2): 239–62.

Schumacher, Bernard N. 2014. Jean-Paul Sartre: Das Sein und das Nichts. Kindle Ausgabe. Walter de Gruyter.

Stahl, Stefanie. 2020. The Child in You: The Breakthrough Method for Bringing Out Your Authentic Self. London: Penguin.

Steiner, John. 2015. “Seeing and being seen: Shame in the clinical situation.” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 96 (6): 1589–601.

Stemper, Dirk. 2023. Toxische Schuld und Scham: Das Arbeitsbuch für Selbstwertgefühl. Berlin: Psychologie Halensee.

Stolorow, Robert D. 2010. “The Shame Family: An Outline of the Phenomenology of Patterns of Emotional Experience That Have Shame at Their Core.” International Journal of Psychoanalytic Self Psychology 5 (3): 367–68.

Stolorow, Robert D. 2011. “Toward Greater Authenticity: From Shame to Existential Guilt, Anxiety, and Grief.” International Journal of Psychoanalytic Self Psychology 6 (2): 285–87.

Tangney, June P. 2002. “Perfectionism and the Self-Conscious Emotions: Shame, Guilt, Embarrassment, and Pride.” In Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment, 199–215. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Tangney, June P., Roland S. Miller, Laura Flicker, and Deborah H. Barlow. 1996. “Are shame, guilt, and embarrassment distinct emotions?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70 (6): 1256–69.

Tiedemann, Jens L. 2008. “Die intersubjektive Natur der Scham.” Forum der Psychoanalyse 24 (3): 246–63.

Van Vliet, K. Jessica. 2008. “Shame and resilience in adulthood: A grounded theory study.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 55 (2): 233–45.

Wells, Marolyn, Cheryl Glickauf-Hughes, and Rebecca Jones. 1999. “Codependency: A grass roots construct’s relationship to shame-proneness, low self-esteem, and childhood parentification.” The American Journal of Family Therapy 27 (1): 63–71.

Williams, Bernard. 2015. Scham, Schuld und Notwendigkeit: Eine Wiederbelebung antiker Begriffe der Moral. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Wurmser, Leon. 2011. Die Maske der Scham: Die Psychoanalyse von Schamaffekten und Schamkonflikten. Berlin – Heidelberg: Springer.