Public shaming: from the Middle Ages to the Digital Era

- Public shaming: from the Middle Ages to the Digital Era

- Introduction

- Social aspects of shame

- Individual aspects of shame

- The connection between interpersonal shame and social/individual aspects

- The history of public shaming

- Codex Hammurabi

- Old Testament interpretation of the law

- Antiquity

- The penal society

- Standards and shaming of deviation

- Psychopolitics

- The surveillance and nanny state

- The role of social media

- The dynamics of attention economy, anonymity and group dynamics

- Public shaming and political discourse

- Public discrimination

- Propaganda and manipulation

- The spectator democracy

Introduction

Shame is a profound, interpersonal emotion that encompasses both individual and social aspects and is a central human experience. It is an emotional response that is closely linked to the perception of the self by others and the fear of social rejection. Shame can be understood as a signal informing us when we risk jeopardising our social bonds or damaging our social standing within a community.

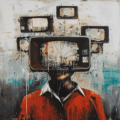

The growing prominence of shaming in public discourse and social media raises essential questions about its impact on individuals, the social fabric and political systems. Shaming as a tool of social control and norm enforcement always risks causing harm, polarising discourse and further dividing political camps. In this context, gaining a deeper understanding of the mechanisms, effects and ethical considerations surrounding personally and politically motivated public shaming is crucial.

Social aspects of shame

On a social level, shaming serves to enforce social norms and values. The experience of shame or even the fear of shame prevents individuals from engaging in behaviour considered inappropriate or unacceptable by their community or society. In this sense, shame also acts as a form of social control that maintains a given social order.

The social dimension of shame is also anchored in how it is experienced and expressed publicly. Public shaming, whether through personal or political shaming, exploits the human fear of social exclusion and loss of reputation to instigate behavioural change or send specific messages. These practices have negative consequences, deepening social divisions and fuelling hostility and resentment.

Individual aspects of shame

On an individual level, shame is closely linked to self-esteem and self-perception. Experiencing intense shame leads to feelings of worthlessness, isolation and failure. Internal self-assessment processes and external criticism or rejection can trigger these emotions.

Those affected react to shame with various strategies, from avoidance and compensation to eliminating the underlying causes of their feelings of shame. Dealing constructively with shame requires critically examining one’s own values and beliefs and the social norms that give rise to these feelings.

The connection between interpersonal shame and its social and individual aspects illustrates the complexity of this feeling. Shame is not only an internal experience but also a phenomenon that is shaped by social interactions and expectations within a community. How societies and individuals deal with shame has far-reaching implications for social cohesion, personal development, and well-being.

To minimize the harmful effects of shame and promote its potentially positive role as a catalyst for personal growth and social change, developing a deeper understanding of the causes and contexts of feelings of shame is crucial. That requires an open and empathic discussion about shame, a critical evaluation of the mechanisms of shaming in society and individual reflection on how we experience and respond to shame.

The history of public shaming

Public shaming has a long history and has been used in different cultures and eras for social control and punishment.

The practices of public punishment and shaming and the marking of individuals as punishment for offences have deep-rooted historical origins dating back to antiquity and ancient civilizations. The Code of Hammurabi, the Old Testament conception of law and various traditions in antiquity offer insights into the development of legal norms and penal practices.

Codex Hammurabi

The Code of Hammurabi, one of the oldest known codes of law, dates back to ancient Mesopotamia around 1754 BC and was introduced by Hammurabi, the sixth king of Babylon. This code contains laws and ordinances governing various aspects of daily life, including punishments for offences. Many punishments laid down in the code are based on the principle of talion law – “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” – and include corporal punishment for certain crimes. Although the Code of Hammurabi does not explicitly address the practice of public shaming, it lays the foundation for the idea of proportional retribution and the public demonstration of justice, which was further developed in later penal systems.

Old Testament interpretation of the law

The Old Testament conception of law, particularly the laws recorded in the books of Leviticus and Deuteronomy, also reflects a society in which punishments and purification rituals were carried out publicly to maintain both divine order and social harmony. Like the Code of Hammurabi, principles of retribution and public rebuke for offences are also found here. The Old Testament texts emphasize the importance of community and adherence to divine commandments, with punishments often reinforcing moral and legal norms within the community.

Antiquity

In ancient times, especially in Greece and Rome, public punishment and shaming were standard practices for maintaining social order and deterring offences.

Ostracism

In Athens, for example, the practice of ostracism was a form of public ostracism in which citizens considered a threat to the city could be banished for ten years.

Crucifixion

In Rome, criminals, traitors and slaves were often publicly flogged, crucified or thrown to the animals in the Circus Maximus as a form of deterrence and demonstration of state power.

The penal society

These few examples show how the concepts of law, justice and punishment are deeply rooted in the history of society and that public punishment and shaming have long served as a means of exercising power, enforcing social norms and deterring offences. The development of these practices reflects changes in social values, notions of justice and the structures of social order.

Public executions

Public executions were another form of extreme public shaming and punishment that was practised in many cultures for centuries. Carrying out the death penalty in front of the public was not only intended to punish the convicted person for their offence but also to send a strong deterrent message to the community. Public executions were, therefore, large-scale events that not only served to carry out a sentence but, as a form of entertainment for the crowd, were intended to create a wider audience for the message sent out by the authorities.

Other forms of throat justice for public shaming

In addition to public execution, other forms of punishment in the history of criminal justice served the purpose of public shaming.

The pillory

The pillory and public executions are two historical examples that show how shaming was also used in the Middle Ages and early modern times to enforce norms and laws and to discipline dissenters.

It was a rack on which offenders were shackled and put on public display. This form of punishment was widespread in medieval and early modern European societies and served to expose the shamed to the community for their offences. The display served as punishment for various crimes, from theft and fraud to moral misconduct. The purpose of the public exhibition was not only to punish the offender but also to present a deterrent example to the community and reinforce social norms.

The neck iron

A metal device was placed around the convict’s neck, often with an inscription of the offence committed. The convict had to wear this iron publicly, which publicised his shame.

The mask of shame

A mask that the shamed person had to wear and which was often grotesquely designed to ridicule the wearer. It was used for various offences, especially gossip or blasphemy.

The cucking stool

The baker’s seesaw was used to punish bakers who baked bread that was too small or stretched the flour. The baker was locked in a cage of shame at one end of a long beam, which functioned like a seesaw, and then dipped several times in water or faeces. This type of punishment was staged like a public festival and was aimed at publicly shaming the baker and, at the same time, encouraging other guild members to ensure the quality of their goods.

Marks of shame

Marks of dishonour could be inflicted either in the form of a specific clothing mark (Latin: nota infamiae) or of amputations, scars or burn marks (Latin: notam infamiae cauterio inurere alicui: to burn a mark of dishonour on the forehead). The purpose of a mark of shame is, on the one hand, the punishment itself, which is associated with pain in the case of corporal punishment. At the same time, however, a mark of shame is used to warn fellow citizens of a condemned person. There is often a symbolic connection between a crime or offence committed and the nature of the mark of shame. (For example, the right hand of thieves or perjurers was chopped off).

Branding

Branding was a form of corporal punishment in which a red-hot iron or other heat source was used to burn a specific mark or symbol into the skin of the condemned person. This mark permanently marked the person with evidence of their offence or status as a criminal, slave or traitor. Branding was often applied to visible areas such as the forehead, cheeks or hands to ensure the stigma was visible to others. The practice served not only as a punishment for the offence committed but also as a means of deterring others, permanently marking the punished person, and making their reintegration into society more difficult.

Ear slitting

The slitting of ears, which gave rise to the word “slit ear” – used since the 19th century to describe a dishonest, cunning person – was another form of corporal punishment for public humiliation. The ear of the condemned person was partially or entirely cut off or slit open. As with branding, this punishment served as a permanent sign of shame, signalling the offence committed and the low social status of the punished person. Ear slashing was used for various offences, including theft, fraud or as a punishment for slaves who had tried to escape. It was a visually conspicuous punishment aimed at humiliating the punished person in front of the community and deterring others from similar misbehaviour.

The Ship of Fools

Although used metaphorically in literature and art, the Ship of Fools refers to putting people with undesirable behaviour (fools) on a ship and banishing them from the community, which was the ultimate form of public shaming and ostracism.

The Jewish Star

The practice of marks of shame as a means of public discrimination and shaming of individuals finds a modern and tragic equivalent in the use of the Jewish Star in the Third Reich.

From 1941, Jews in German-occupied Europe were forced to visibly wear a yellow star labelled “Jew” on their clothing. This measure was aimed at publicly identifying Jews, isolating them from the rest of the population and labelling them as targets for persecution and violence. The Jewish Star served not only as a physical sign of exclusion and humiliation but also as a means of dehumanising the Jewish community and portraying its members as inferior.

The use of the Jewish Star in the Third Reich is an example of the most extreme and devastating consequences that the practices of public labelling and shaming can have. While the historical forms of the mark of shame marked individual offences, the Jewish Star symbolised a state-sanctioned policy of racial persecution and genocide. These measures were part of the broader Nazi strategy to stigmatise, disenfranchise and ultimately exterminate entire population groups.

The connection between these historical and modern practices of labelling and shaming shows the dark side of such methods, especially when authoritarian regimes use them for purposes of discrimination and genocide. It underlines the need to respect all individuals’ dignity and rights and recognise the dangers that arise when state power is misused to promote hatred and intolerance.

From public shaming to a disciplinary society

The exercise of power, control and the body are interwoven with punishment and surveillance in shaming practices and become more subtle and internalised over time. That shows that the use of shaming to enforce social norms and punish deviants is a deeply rooted practice that has evolved over centuries and continues to persist.

Public shaming through torture, executions and the show trial served to maintain social order. The criminal was seen as an enemy of society whose offences had to be atoned for through corporal punishment and public humiliation. These practices served the function of retribution and primarily served as a deterrent to restore moral order.

The public display of the criminal and the associated shame was intended to discipline the offender and send a clear message to the community about the consequences of misbehaviour. These practices were based on the assumption that the fear of social ostracism and loss of reputation would deter people from committing crimes. In pre-modern society, punishment was firmly focused on the body and its public spectacles were intended to demonstrate the sovereign’s power and enforce the state’s laws.

With the establishment of the prison as the central penal institution, these dynamics changed fundamentally. Torture and public executions increasingly disappeared from the social stage and were replaced by more subtle forms of control and discipline. The prison, along with other institutions such as the school, army, factory or hospital, epitomises what Foucault called the “confiscation” of the individual.

Standards and shaming of deviation

The institutions of confiscation exercise their power not only through physical confinement but primarily through the systematic regulation and surveillance of everyday life. They aim to gain control over the body, sexuality and interpersonal relationships and thereby shape society. They not only create prohibitions but, above all, norms that prescribe and enforce a specific image of society and a social structure by, among other things, marking and publicly shaming deviations.

In this context, public shaming is sustained by an uninterrupted standardisation that orders social life through a sequence of judgements, punishments and rewards. The disciplinary society makes use of a judging authority that is omnipresent and whose judgement affects all aspects of life. The increasing individualisation in modern society goes hand in hand with increased standardisation and surveillance.

In today’s society, personal and political shaming based on this standardisation has once again become ubiquitous phenomena that play a central role in private and public discourse.

Personal shaming

Personal shaming, the practice of publicly exposing or criticising individuals for their beliefs, behaviour or characteristics, has a profound psychological impact on those affected and seeks to enforce the shaping of certain social norms and values.

Political shaming

Political shaming, on the other hand, criticising and condemning groups or governments for their political values, actions, or policies, plays a crucial role in the way political discourse is currently conducted, opinions are formed, and power relations are negotiated.

New forms of capitalism and state surveillance have developed in modern society that are closely linked to neoliberal ideologies.

Psychopolitics

The term “psychopolitics” and the concept of the “surveillance and nanny state” offer insights into these developments. They reflect how economic and political systems are increasingly intervening in individuals’ personal and psychological lives.

The surveillance and nanny state

The concept of the surveillance and nanny state refers to expanding state surveillance and interventionist policies aimed at controlling and regulating citizens’ behaviour. While the term ‘surveillance state’ emphasises the increasing collection and analysis of data about citizens through technologies such as CCTV, data collection and processing, and monitoring programmes, the ‘nanny state’ refers to state intervention in personal choices and lifestyles under the pretext of protecting public health and safety. Examples include laws and regulations that restrict the consumption of tobacco, alcohol and unhealthy foods, or the enforcement of vaccinations and other health-related measures. Such methods limit personal freedom and undermine individual responsibility by paternalistically telling citizens how they should live.

In all areas, public methods of personal and political shaming are used to enforce good behaviour and devalue information and attitudes that do not conform to the government.

Psychopolitics and the surveillance and nanny state reflect the complex interactions between neoliberal economic practices, state power and individual autonomy in contemporary society. They raise important questions about the limits of market forces and state intervention in personal lives and call for a critical examination of the impact of these developments on the social order and the well-being of individuals.

Against this backdrop, the rise of social media has notably contributed to the popularisation of feelings of shame. Online platforms offer visibility and anonymity, making it easier for people to publicly shame others without revealing their identity. Shaming has become a defining aspect of digital communities where individuals define themselves by whom they shame. Similarly, the attention economy of social media incentivises shaming and counter-shaming as it keeps people engaged and is profitable for the companies that operate these platforms.

The dynamics of attention economy, anonymity and group dynamics

The dynamics between attention economy, anonymity and group dynamics play a crucial role in the modern digital landscape, especially in social media and online forums. These three elements interact in complex ways and influence the behaviour of individuals and the way information is disseminated and discussed.

Attention economy

Human attention has become a valuable and scarce resource in a world flooded with information. Online platforms and media companies compete for this attention as it is directly linked to advertising revenue and commercial success. Controversial content that triggers emotions tends to generate more attention, leading to a preference for sensationalist or polarising news. This dynamic also influences political discourse by reinforcing extreme positions and undermining nuanced discussions.

Anonymity

Anonymity on the internet allows users to act without revealing their true identity. Whilst it offers positive aspects such as privacy and the freedom to express unpopular opinions without fear of retribution, it also has downsides. Anonymity can lead to disinhibition, with individuals behaving in ways they avoid in face-to-face interactions. That can lower the threshold for aggressive behaviour, hate speech and online bullying and create a toxic environment in which constructive debate becomes jeopardized.

Group dynamics

Group dynamics in digital spaces are often reinforced by echo chambers and filter bubbles, in which users primarily encounter information and opinions that reflect their own views. In addition to “virality”, this leads to reinforcing prejudices, a polarisation of opinions and a decrease in tolerance towards dissenting views. Peer pressure and the desire to belong motivate individuals to follow dominant opinions or behaviours within their group, even if they are extreme or harmful.

The interaction between the attention economy, anonymity and group dynamics has far-reaching consequences for public debate and democratic coexistence. On the one hand, it promotes a culture in which sensational and polarising content is rewarded. At the same time, anonymity virtually invites the shaming of deviant behaviour, and group dynamics encourage discrimination against dissenters through in-out thinking.

Public shaming and political discourse

In the media and on social platforms, public shaming is increasingly being used in an uninhibited manner to discredit political opponents by ridiculing them or undermining their credibility. This tactic aims to oust certain opinions and perspectives from public discourse by penalising them with negative consequences. The result is narrowing the political discourse space in which only “acceptable” opinions can be expressed without risk of shaming or exclusion.

Public discrimination

Public discrimination, whether through hate speech, targeted shaming or the stigmatisation of specific communities, further contributes to the fragmentation of society. These practices discriminate and isolate those affected and promote a culture of fear and mistrust. Publicly labelling and devaluing certain groups or individuals creates a climate in which differences are emphasised and similarities are minimised. That makes it more difficult to develop empathy and understanding across social or political boundaries.

Propaganda and manipulation

Propaganda and manipulative content aim to sway public opinion in a particular direction by spreading selective information, half-truths or deliberately false information. These techniques fuel mistrust and scepticism towards specific groups, political opponents or ideologies. Viewing “others” as hostile or alien destroys the basis for solidarity and collective action.

The use of propaganda, manipulation and public discrimination by the media and social platforms therefore contributes significantly to the division and desolidarisation of society. These practices ultimately promote the individual atomisation of society, which undermines collective awareness and the capacity for collective action. At the heart of this dynamic is the deliberate fragmentation of the social fabric, achieved through the dissemination of polarising messages and the stigmatisation of groups or opinions.

As a result, individuals feel increasingly alienated from society and less willing to commit to collective goals or the common good. That weakens the essential foundations of democracy: participation and the belief in the possibility of change through collective action.

The spectator democracy

This narrowing of the discourse space undermines the free formation of opinion in a democracy. In such a “spectator democracy”, citizens are infantilised into passive observers and consumers through shaming and discouraged from actively participating in the political process. The result is apathy and alienation towards the political system. At the same time, populism gains increasing acceptance, and the deep state and non-transparent power structures, which operate behind the scenes and make decisions that often have little to do with the issues and promises of the cartel parties presented in election spectacles, are strengthened.

One crucial aspect is using shaming as a political strategy by politicians themselves. Federal politicians are instrumentalising shame to stir up anger against the opposition and loyalty among their supporters. The latest, since the Covid pandemic, they have increasingly relied on public shaming in legacy media and social platforms to define what can be thought and said to achieve their goals. Lobby and government-funded propaganda platforms such as Correctiv provide the ammunition for the war of “moral outrage”, which aims to purge the public discourse of anything that runs counter to government policy. No other means are used so successfully and, at the same time, so undetected. The intention behind the moral outrage and shaming of “dissenters” usually goes unnoticed and is rarely criticised. It flies under the radar and thus becomes a much more dangerous weapon for manipulating the public, alongside the creation of fear. It imposes the concerns of one social group on an entire society.

These practices narrow the space for open and constructive political discussion and transform society into a “spectator democracy” in which elections become a spectacle rather than an expression of the people’s will. This development favours structures and actors often referred to as the “deep state” – a network of institutions within the government and the military, but also from business and other sectors that exert power and influence independently of democratic processes.

However, people who feel attacked or shamed by the media or critics will easily rally around a politician who appears to be defending them against this perceived attack. This dynamic creates a sense of polarisation between those who support the populist politician and those who criticise them. Right-wing populist politicians, therefore, also use shaming systematically and strategically to win votes, using shaming and scapegoating as a tactic.

The rise of right-wing populist politics is therefore linked to a fundamental struggle for recognition and the perception of disrespect among elites and social groups and the shaming of certain sections of society. Sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild linked support for Trump to the “struggle to feel seen and respected”, rooted in dwindling job security and perceived threats to pride in one’s identity. The feeling of being shamed by urban or educated elites and the media increases the appeal of politicians who address these concerns and pledge to restore respect.

Shaming in politics is mainly characterised by the use of labels and derogatory remarks. Recent verbal gaffes by members of the government in public (“pied piper” or “fallen angel from hell”) show how these labels can backfire and be reinterpreted as badges of honour. The shaming leads to a righteous counter-reaction to the complete lack of self-reflection on the part of those being shamed.

Contemporary politics elevates shaming to a political strategy in the neoliberal transformation. Shaming dissenters is intended to mobilise and polarise supporters by tapping into feelings of perceived disrespect and the desire for recognition. Shaming is designed to serve as an alibi for politicians in the governing coalition and divert attention from examining their role in social issues. Instead of examining themselves, these politicians and opinion leaders focus on evading responsibility for their own contribution to societal problems.

It is necessary to critically scrutinise the mechanisms of public shaming and the staging of politics in the media and to find ways to involve citizens more closely in the political process again to combat these developments. That also includes protecting and expanding the space for a diverse and open political discourse in which different opinions and perspectives can be expressed without fear of shaming or exclusion. That is the only way to prevent democracy from being undermined and to return it to a lively, participatory process.

Literature:

Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Bach, Bo, and Joan M. Farrell. 2018. “Schemas and modes in borderline personality disorder: The mistrustful, shameful, angry, impulsive, and unhappy child.” Psychiatry Research 259 323–29.

Boddice, Rob. 2019. A History of Feelings. London: Reaktion Books.

De Paola, Heitor. 2001. “Envy, jealousy and shame.” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 82 381–84.

Deleuze, Gilles. 2020. “Postskriptum Über Die Kontrollgesellschaften.” In Unterhandlungen, 254–62. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

English, Fanita. 1975. “Shame and social control.” Transactional Analysis Journal 5 (1): 24–28.

Foucault, Michel. 1973. Wahnsinn und Gesellschaft: Eine Geschichte des Wahns im Zeitalter der Vernunft. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Überwachen und Strafen: Die Geburt des Gefängnisses. Stuttgart: Suhrkamp.

Foucault, Michel. 1978. Dispositive der Macht: Über Sexualität, Wissen und Wahrheit. Merve.

Foucault, Michel. 2022. Die Geburt Der Biopolitik. Stuttgart: Suhrkamp.

Han, Byung-Chul. 2014. Psychopolitik: Neoliberalismus und die neuen Machttechniken. Kindle Ausgabe. S. Fischer Verlag.

Hirsch, Mathias. 2008. “Scham und Schuld – Sein und Tun.” Psychotherapeut 53 (3): 177–84.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 2018. Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. New York: The New Press.

Klein, Melanie. 1984. Love, Guilt, and Reparation, and Other Works, 1921-1945. New York: The Free Press.

Morrison, Andrew P. 1983. “Shame, Ideal Self, and Narcissism.” Contemporary Psychoanalysis 19 (2): 295–318.

Rafaeli, Eshkol, Jeffrey E. Young, and David P. Bernstein. 2013. Schematherapie. Junfermann Verlag GmbH.

Roediger, Eckhard. 2016. Schematherapie: Grundlagen, Modell Und Praxis. Stuttgart: Schattauer.

Scheff, Thomas J. 2000. “Shame and the social bond: a sociological theory.” Sociological Theory 18 (1): 84–99.

Tangney, June P. 2002. “Perfectionism and the Self-Conscious Emotions: Shame, Guilt, Embarrassment, and Pride.” In Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment, 199–215. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Tiedemann, Jens L. 2008. “Die intersubjektive Natur der Scham.” Forum der Psychoanalyse 24 (3): 246–63.

Williams, Bernard. 2015. Scham, Schuld und Notwendigkeit: Eine Wiederbelebung Antiker Begriffe Der Moral. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Wurmser, Leon. 2011. Die Maske der Scham: Die Psychoanalyse von Schamaffekten und Schamkonflikten. Berlin – Heidelberg: Springer.