- Navigating the Landscape of Public Shaming: Strategies for Resilience

- Introduction

- Definitions and demarcations

- Personal shaming

- Political shaming

- Shaming narratives and power structures

- The Psychology Behind Shaming: Power, Insecurity, and the Need for ControlPower

- Alibi

- Uncertainty

- Enemy images

- Craving for recognition

- Practice

- Exercises

Introduction

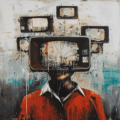

Following last week’s post on the history of public shaming, the following blog post aims to develop a psychological understanding of these complex issues by exploring the psychological roots as well as the social and political implications of public shaming. It is intended to provide insights that encourage reflection and possibly constructive engagement with these pervasive phenomena of our time.

Definitions and demarcations

Personal shaming

Personal shaming refers to the act of publicly humiliating or criticising a person for beliefs, actions, or characteristics, intending to expose them and make them feel despicable and unworthy. This type of shaming, a form of bullying, occurs in different contexts, within families, communities, or online platforms. Personal shaming deliberately reduces someone to faults, weaknesses, or perceived shortcomings. It is fuelled by anger, arrogance, or the desire to belittle someone.

Personal shaming takes place in a variety of contexts and can be caused by different triggers. It often occurs in social relationships and communities where individual actions or character traits are at odds with expected norms or values. In the family, at work or within peer groups, personal shaming can occur in response to behaviour that is seen as inappropriate, unethical, or disappointing. Online platforms have created a new arena for personal shaming, where comments, images or videos considered embarrassing or offensive can quickly reach a broad audience and lead to intense shaming. The anonymity of the internet can lower the threshold for shaming comments and increase the intensity and reach of the shaming. Personal shaming is often triggered by the perception that someone is breaking social rules, overstepping personal boundaries, or affecting the well-being of others through their behaviour. The intention behind the shaming – whether to correct, out of anger or as a means of marginalisation – plays a crucial role in its impact on the person concerned.

Personal shaming can take many forms, relating to various aspects of a person’s life. Here are some specific examples:

Social media

One of the most common platforms for personal shaming is the internet, especially social media. An example of this is sharing embarrassing photos or videos without the consent of the person depicted in order to expose or mock them publicly. Spreading rumours or untrue claims about someone on social media can also significantly damage their reputation and self-esteem.

School and workplace

Personal shaming can take the form of mockery, gossip or lies about someone’s abilities, achievements, or personal life in schools or the workplace. Teachers or supervisors who criticise someone in front of others for mistakes or shortcomings without leaving room for constructive debate are also engaging in a form of personal shaming.

Family and friends

Personal shaming also occurs in family or friendly relationships through derogatory comments about appearance, life choices or behaviour. Such comments, often made under the guise of “concern” or “honest opinion”, damage the self-image and self-esteem of those affected.

The public

Personal shaming also happens in public when someone is loudly belittled because of their behaviour or appearance, for example, in a restaurant or shop. This public exposure causes deep shame and embarrassment and has long-term effects on self-confidence.

Online evaluation platforms

Negative reviews or feedback about someone’s professional performance or services on online platforms can also constitute a form of personal shaming, especially in the case of personal and unobjective criticism.

These examples illustrate how personal shaming can occur through different channels and in various areas of life. The effects of personal shaming are often far-reaching and have a significant impact on the self-esteem, mental health and social relationships of the person affected.

Political shaming

In the case of political shaming, on the other hand, the purpose of shaming is to ridicule and condemn individuals or groups for their political beliefs, actions or strategies. It occurs in a broader context, such as public discourse and media coverage. Political shaming highlights differences of opinion in order to exert social pressure or mobilise support for particular political goals. It can be directed against politicians, public figures, social groups or entire political movements and attempts to manipulate public opinion, draw attention or bring about political change.

Political shaming covers a wide range of practices. Here are some examples:

Political debates

Parliamentary debates are a traditional platform where politicians use rhetorical means to directly embarrass opponents by questioning their decisions, competence or moral integrity. The aim is to damage the opponent’s public image and strengthen their own position.

Media campaigns

Currently, governments in Western countries use traditional and digital media for massive campaigns against groups, political figures or parties by publicly denouncing their actions, statements or political positions. These campaigns try to use viral hashtags to generate attention and build public pressure.

Parodies and satire

For some time now, comedians, satirists, and artists, paid for by governments, have unbearably misused parodies and satirical portrayals to marginalise social groups or to ridicule or devalue political figures and their actions. Exaggeration and humour are used to conceal political interests and publicly shame those affected.

These examples of political shaming show how diverse the methods are with which public shaming is used to exert power and pressure in the political arena. While political shaming as a propaganda component effectively generates attention for specific causes, it also leads to social resistance and division due to its insincerity.

Public Shaming: Understanding the Dynamics

Personal and political shaming both seek to disparage an individual publicly. Personal shaming focuses primarily on the behaviour or character of the individual, while political shaming extends to broader political beliefs, policies, and systemic issues.

Political shaming deliberately distracts from realistic and practical ways to change society and is often an integral part of the propaganda that conjures up supposedly magical solutions to crises. Shaming may offer a short-term “feel good” solution while seeking to prevent long-term change.

Governing parties, in particular, use shaming to blame others, including minorities and critics, and to recruit supporters for their own government policies through political polarisation.

Shaming narratives and power structures

Shaming narratives play a vital role in maintaining and reinforcing political power structures in neoliberalism. These narratives are often subtle and deeply embedded in discourses that emphasise individual responsibility, achievement, and success while minimising or ignoring structural inequalities and power relations. At the core of this dynamic is the use of shaming to promote specific political and economic ideologies and suppress criticism or resistance. External fear of social decline or loss of livelihood is thus transformed into internal fear.

Neoliberalism is, therefore, all about individual responsibility and self-management. Shaming narratives are used to blame people for their failure in a system characterised by structural inequalities. Unemployment, poverty, and social exclusion are portrayed as personal failures rather than the result of economic conditions or political decisions. These narratives reinforce the idea that success is simply a matter of making the right choices and effort and ignore the reality that not all individuals have the same starting conditions or opportunities.

These ideologies are further cemented by shaming individuals who do not conform to neoliberal ideals of success and productivity. The stigmatisation of benefit recipients or marginalised groups serves to increase the acceptance of cuts in social services and legitimise the withdrawal of the state from welfare provision. At the same time, the ideal of the entrepreneurial self is promoted, which is flexible, self-responsible and constantly endeavouring to improve its marketability.

Shaming narratives also serve to suppress criticism of neoliberal policies and practices. By branding protesters or critics as lazy, uninformed or disturbers of the public peace, their concerns are discredited and marginalised. That helps to maintain the status quo and weaken potential resistance.

In the context of digitalisation, neoliberal propaganda is fuelling a dramatic increase in fanatical group-based hostility, including hate speech and extreme ideologies. The increase in these narratives leads to the entrenchment of shame and negative prejudices against certain groups.

The Psychology Behind Shaming: Power, Insecurity, and the Need for ControlPower

The psychological root of the popularity of shaming among perpetrators is the need for validation and respect. Shaming techniques can also be motivated by the desire to feel powerful. (On the other hand, feelings of shame result from a perceived loss of social attractiveness and serve as a warning signal that one’s own power and status in society are under threat).

Shaming is popular with political actors because it promotes the joint condemnation of opponents. The result is a feeling of being in, an illusion of solidarity. Another reason is that shaming can serve as an alibi to divert attention away from oneself. Shaming others thus spares self-reflection or responsibility for one’s own actions in a particular situation.

Alibi

This motive can often be observed in a personal context. The individual denies their own responsibility. Verbal abuse shifts blame and responsibility onto others. In this way, everyone can avoid self-observation and self-reflection and not have to face tough questions about their roles and contributions to a situation or problem. This denial of self-responsibility helps to maintain a positive self-image.

In politics, too, shaming political opponents or their supporters serves to deny responsibility to governments that have themselves played the most significant role in creating or perpetuating the problems in question. The accusations prevent scrutiny of the government’s actions that caused or exacerbated the problems.

Uncertainty

Erich Fromm, social psychologist and philosopher, coined the term authoritarian character to describe the personality structure of individuals who tend to idealise and submit to authority while simultaneously stepping down and oppressing weaker or dissenting individuals. This concept is intricately linked to the psychology of public shaming, particularly in the way it is used against dissenters.

The authoritarian character tends towards rigid black-and-white thought patterns that break down complex social realities into simple hierarchies and orders. To combat those perceived as outside this order or as its opponents, they will use any means at their disposal – but rarely open discussion due to their cowardice. Public shaming serves these characters, when they feel secure as subjects of power or in the majority, as a tool to enforce conformity and strengthen their position within the assumed hierarchy.

The psychology behind this public shaming of dissenters stems from the need to overcome insecurities and fears by drawing a clear line between “us” and “them. By shaming dissenting opinions, the authoritarian character seeks to validate their own worldview while creating an illusion of superiority and security. This process reinforces social cohesion within the group that shares the relevant norms while marginalising those perceived as a threat to this cohesion.

Enemy images

While Hans Blumenberg did not directly contribute to the concept of authoritarianism as initially developed by Erich Fromm and later by Theodor W. Adorno and other members of the Frankfurt School, his work nevertheless offers valuable insights into the connections between authority, myth and rationality that are important for an understanding of authoritarianism and the psychology of public shaming of dissent.

In particular, his comprehensive research Metaphors and Myths contributes to understanding the psychological dynamics that underlie authoritarianism and public shaming. Blumenberg argues that myths and metaphorical language address basic human needs to make the world understandable and manageable. That makes them attractive to authoritarian characters who, as just described, favour simple, black-and-white worldviews and divide complex realities into good/evil or us/them categories.

Whether pandemics, climate or wars, the propaganda of Western governments since the Covid pandemic has been extremely fond of using strong metaphors and myths in its political rhetoric to establish authority on the one hand and to shame those who think differently on the other publicly. Like authoritarian leaders, they use the language of myth – such as the idea of a threatened community that must be protected from external or internal enemies – to consolidate their power and draw a clear dividing line between “us” and “the others”. This rhetorical strategy appeals to deep-rooted fears and needs for security and belonging and promotes an uncritical acceptance of authority.

The public shaming of dissenters in this context serves not only to suppress dissent but also to strengthen the collective identity of the “ingroup” by differentiating it from the “outgroup”. By portraying those who dissent from the official line as morally reprehensible, dangerous, or unworthy, this authoritarian rhetoric and its adherents utilise the mechanisms of shaming to strengthen the social cohesion of their followers while undermining the foundations for rational discourse and pluralistic social structures. It uses these narrative structures to consolidate power and weaken opposition.

It exploits the feeling of being overwhelmed when everything seems to happen “all at once” or when past events feel just as immediate as current ones. Then, suddenly, lifetime is confronted with world time. World time represents objective, historical time encompassing major social, political, and ecological changes and events. It is independent of individual experience and progresses without considering personal wishes, hopes or fears. On the other hand, individual time is the personal experience of time, which is characterised by one’s own life, experiences, and personal development.

The relationship between world time (Weltzeit) and individual time (Lebenszeit), as can be seen in the reflections on authoritarian character and the psychology of public shaming of dissenters, plays a crucial role in understanding the dynamics that lead authoritarian personalities to fight dissenters. This contrast between the personal experience of time and objective historical time harbours a profound tension that can both encourage and reinforce authoritarian tendencies.

However, authoritarian characters strongly need control and order that extends to their immediate environment and the larger social order. The discrepancy between world time, which is beyond their control, and individual time, in which they can exert power and influence, creates anxiety and insecurity. Authoritarian characters seek to establish rigid structures and clear distinctions between “us” and “them” to manage this uncertainty.

Fighting dissent is an attempt to control the unpredictability of the world’s times and to transfer their own idea of order to the social level. By publicly shaming or fighting individuals or groups who hold dissenting opinions, they attempt to create a homogenous social order that minimises their own insecurity and satisfies their need for control. This strategy allows them to create an illusion of unity and stability by reducing the complexity and diversity of human experiences and perspectives.

Craving for recognition

It is not only the supporters of the radical climate protection movement who find it difficult to accept that the best state of the world will only ever materialise in an unattainable future. But this is precisely the result of the different relationship between people’s lifetimes and the course of history. This disproportion between the time of life and the time of the world creates a feeling of unease, a loss of meaning and resentment, which prompts some people to look for new narratives – metaphors or even mythologies – to give their existence a supra-individual meaning.

There is, therefore, an astonishing tendency for young people to passionately believe in the end of the world and how it will unreasonably affect their lives. In doing so, they project their own desolation onto an imagined state of the world that results from the bleakness and irrelevance of their bourgeois reality. Consequently, they discover all kinds of threats from the older generation or “fossil fuels”. Thus, the supposed end of the world serves as justification for their demand to enforce their mythologised ideas of the future – by increasingly radical means – during their lifetime. For all its radicalism and actionism, deep down, this ideology only has the somewhat childish desire to experience complete liberation from all afflictions through the final victory of the good in their own lifetime. To this end, every means is justified to smash everything that exists and to expose and silence every opponent of opinion.

The mythical, oversimplified black-and-white view of the world inevitably leads to black-and-white solutions and polarisation, with debates revolving around either/or rather than multi-layered solutions. Those who conduct the media and political discourse in terms of a mythical ultimate battle between good and evil – where they themselves are, of course, the representatives of good – only want to give meaning to publicly held opinions anchored in this old dualistic narrative. The unwavering commitment to using all available means against the forces of evil has always ruled out any possibility of alternative goals and regards its own actions as the only right thing to do – shame on anyone who questions this.

In such a framework, arrogant self-righteousness falls into the trap of unhistoricality and absolute narcissism. The argument that a situation can no longer be simply accepted because it has been accepted for a long time is plausible but nevertheless illogical. Anyone who demands a complete dismantling of the current situation must prove their demand is justified. Belief is not enough, nor are accusations, labelling and shaming of opponents. Consequently, the egocentric lack of historical reference only makes the way out of the current crises seem easy. Ultimately, it leads to harmful results.

The tension between world time and individual time provides fertile ground for authoritarian tendencies and the practice of public shaming of dissenters. By attempting to control the dynamics of world time by combating deviations in individual time, authoritarian characters merely reveal their deep insecurity and unease about the unpredictability and complexity of the modern world. This behaviour not only undermines the pluralistic foundations of democracy but also reinforces alienation and polarisation within society by limiting the possibility of open, respectful and diverse discourse.

Transforming Shame into Strength: Tools for Personal Empowerment

Individuals can recognise and challenge social and cultural beliefs contributing to shame by engaging in critical awareness and consciousness-raising processes. That includes questions such as “Who am I?”, “Who says so?”, “Who benefits from this definition?” and “What needs to change and how?” in relation to an experience of shame. They help recognise social and cultural beliefs that contribute to shame and question how social and cultural forces shape one’s experiences. That allows those affected to relate their subjective experiences to broader social and cultural issues, deconstructing and contextualising shame. Questions such as “Who am I?”, “Who says so?”, “Who benefits from this definition?” and “What needs to change and how?” challenge prevailing narratives and power structures that enable shaming. This type of questioning will regularly demonstrate that experiences of shame are not only caused by personal failings but are characterised by broader collective issues. It allows people to normalise their own experiences and recognise the social and cultural expectations that narrowly define certain categories such as appearance, body image, sexuality, family, or success. By critically examining these beliefs, norms and values that underpin experiences of shame, individuals can gain a deeper understanding of how these cultural constructs influence their sense of self-worth and acceptance.

It is essential to dissect public shaming tactics and connect them to the broader societal problems rather than internalising them. In this way, it becomes recognisable that shame is always a psychosocial and cultural construct. This perspective enables those affected to question narratives that attempt to label them as inherently evil or flawed. Instead, viewing targeted shaming as linked to social norms and expectations is crucial.

In addition, those affected need to examine their own thoughts and assumptions, challenge false or distorted beliefs and develop constructive self-assessments. Self-compassion, self-acceptance and forgiveness are also crucial in this context when it comes to resisting and empowering oneself against public shaming.

Practice

Support for

Being together or talking to other sufferers who have been through similar situations is an effective strategy for overcoming shame. Such people provide support, empathy, and belonging and can help overcome the pain of shame and realise that no one is alone with such experiences.

Realisation

Shame resilience theory states that critical awareness is essential to overcoming public shaming. That requires recognising and challenging social and cultural beliefs that contribute to shame and personal vulnerabilities that make people susceptible to shaming.

Self-acceptance

By opening up to your own vulnerability and accepting the experience of shame, you can develop greater empathy for yourself and others. Shifting from shame to self-acceptance allows for personal growth.

Distance

Keep your distance from people and communities that try to shame you. In some cases, this may even mean that you have to change your social environment or move to a new neighbourhood or city. Distance from constant reminders of shame is the basis for a new beginning.

Exercises

Coping with public political or personal shaming requires a deep understanding of the psychological mechanisms that control our reactions to negative experiences.

Here are some exercises that can help minimise the personal impact and promote shame resilience. They are aimed at recognising and questioning automatic thoughts and increasing awareness.

Reflection

– Goal: Strengthen self-awareness and identify patterns.

– HOW-TO: Take time each day to reflect on your thoughts, feelings and behaviour. Try to recognise patterns that lead to negative emotions.

Thought log

– Aim: Recognising and challenging negative automatic thoughts.

– HOW-TO: Keep a diary in which you note down automatic negative thoughts as soon as they occur. Write down the situation, the thought, the emotional reaction and alternative, positive thoughts.

Change of perspective

– Objective: To develop empathy and understanding of different points of view.

– HOW-TO: Imagine someone else in the shaming situation. How would they think and feel? What advice would they give you?

Body awareness

– Aim: to develop a positive body awareness and strengthen the self.

– HOW-TO: Use daily physical activity, mindfulness, or yoga exercises to connect to your body and your strength.

Visualisation

– Goal: Mental strengthening through positive visualisation.

– HOW-TO: Imagine how you successfully deal with tricky situations and achieve success.

Implementing such exercises in everyday life requires strength and patience. Take small steps and concentrate on one exercise before moving on to the next. Support from a therapist or coach can also be valuable to apply and adapt such techniques effectively. Above all, never forget that growth takes time.

Literature:

Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Amlinger, Carolin, and Oliver Nachtwey. 2022. Gekränkte Freiheit: Aspekte des libertären Autoritarismus. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Blumenberg, Hans. 2006. Arbeit am Mythos. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Blumenberg, Hans. 2011. Paradigms for a Metaphorology. Ithaka, New York: Cornell University Press.

De Paola, Heitor. 2001. “Envy, jealousy and shame.” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 82 381–84.

Deleuze, Gilles. 2020. “Postskriptum über die Kontrollgesellschaften.” In Unterhandlungen, 254–62. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

English, Fanita. 1975. “Shame and social control.” Transactional Analysis Journal 5 (1): 24–28.

Han, Byung-Chul. 2014. Psychopolitik: Neoliberalismus und die neuen Machttechniken. Kindle Ausgabe. S. Fischer Verlag.

Hirsch, Mathias. 2008. “Scham und Schuld – Sein und Tun.” Psychotherapeut 53 (3): 177–84.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 2018. Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. New York: The New Press.

Klein, Melanie. 1984. Love, Guilt, and Reparation, and Other Works, 1921-1945. New York: The Free Press.

Morrison, Andrew P. 1983. “Shame, Ideal Self, and Narcissism.” Contemporary Psychoanalysis 19 (2): 295–318.

Scheff, Thomas J. 2000. “Shame and the social bond: A sociological theory.” Sociological Theory 18 (1): 84–99.

Tangney, June P. 2002. “Perfectionism and the Self-Conscious Emotions: Shame, Guilt, Embarrassment, and Pride.” In Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment, 199–215. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Tiedemann, Jens L. 2008. “Die intersubjektive Natur der Scham.” Forum der Psychoanalyse 24 (3): 246–63.

Voegelin, Eric. 2012. Science, Politics and Gnosticism: Two Essays. Washington D.C.: Regnery Publishing.

Williams, Bernard. 2015. Scham, Schuld und Notwendigkeit: Eine Wiederbelebung antiker Begriffe der Moral. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Wurmser, Leon. 2011. Die Maske der Scham: Die Psychoanalyse von Schamaffekten und Schamkonflikten. Berlin – Heidelberg: Springer.