Healing the shadows of religious trauma in childhood: A comprehensive Introduction

- Healing the shadows of religious trauma in childhood: A comprehensive Introduction

- 1 Navigating the Shadows: A Comprehensive Introduction to Religious Trauma in Childhood

- 2 Deciphering Religion’s Impact on Childhood: Insights from Claude Lévi-Strauss and Hans Blumenberg

- 3 Unpacking the Triad of Religious Trauma: Faith, Ritual, and Institutional Structures

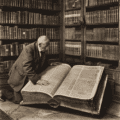

- Claude Lévi-Strauss

- Hans Blumenberg

- 4 The Deep Psychological Consequences of Childhood Religious Trauma

- Do religious communities that are authoritarian, isolationist and fear-based contribute to religious trauma?

- 5 Child development, trauma and religious practices

- 6 Highlighting the Importance of Understanding and Addressing Religious Trauma from Early Years

This introduction is opening a series exploring the complex topic of religion and childhood trauma. Each post will highlight a different aspect.

1.Faith and fear – The tension between fear and faith?

2. Guilt and atonement – the tension between transgression and forgiveness.

3. Shame and the sacred – the tension between experiences of the sacred and shame.

4. Authority and autonomy – the tension between personal freedom and religious authority.

5. Inclusion and exclusion – The tension between belonging and rejection in religious communities.

6. Doubt and faith – the tension between firmness in and betrayal of faith.

7. Healing and growth – ways of overcoming childhood trauma through religion.

You are welcome to share your experiences and leave suggestions for topics in the comments. Whether you struggle with trauma yourself or know someone who has, your voices will help shape this discussion in a comprehensive way.

Former believers react very differently to a diagnosis of religious trauma in childhood. While some feel relief as they finally find an explanation for their suffering, others are faced with the challenge of accepting this connection between their religious past and current psychological problems.

In any case, a diagnosis of religious trauma can help those affected to understand their experiences better and identify ways in which they can deal with the harmful effects of their spiritual past. It can also open the door to seeking professional help and support to aid their recovery and healing.

2 Deciphering Religion’s Impact on Childhood: Insights from Claude Lévi-Strauss and Hans Blumenberg

The conceptual delineation of “religion” and how it can contribute to childhood trauma is complex. Claude Lévi-Strauss and Hans Blumenberg offer deep insights into the nature of religion that help understand the concept of religious trauma in childhood.

Religion is a collective term for various world views, including a belief in supernatural powers and often also in sacred places or objects. In the German-speaking world, religion is used for individual religiosity and collective religious traditions. The teachings of a religion are usually based on the belief in messages from religious founders, prophets or shamans, as well as on intuitive and individual experiences. Spiritual messages or experiences are regarded as revelations in many religions. On the other hand, sceptics and critics of religion seek controllable knowledge through rational explanations. Through norms and regulations, religion influences values, human behaviour, actions, thoughts, and feelings.

3 Unpacking the Triad of Religious Trauma: Faith, Ritual, and Institutional Structures

To understand religious trauma in childhood, one must distinguish between religion as a belief, practice and institution. Each of these dimensions plays a role in the development of trauma.

Religion as faith refers to a believer’s individual conviction and subjective religious life. It encompasses a personal belief in the transcendent, pursuing enlightenment and religious affiliation. This dimension of religion emphasises the spiritual and emotional element of faith.

Religion as a practice refers to the concrete actions, rituals and teachings practised by the followers of a particular religion. It includes ethical principles, moral rules and daily rituals practised in the respective religious community. The ethics practised may vary depending on the interpretation of the religion, e.g., the use of violence or the understanding of religious scriptures.

Religion as an institution refers to the formal structures, organisations and hierarchies within a religious community. That includes religious leaders, dogmas, doctrines and institutions that guide and regulate the beliefs of the faithful. The institutionalisation of religion makes it possible to spread and practice the faith in an organised way.

In every religious community, faith, practice and institution are closely linked and influence each other. Faith forms the basis for the doctrines and beliefs shared by the faithful. These beliefs lead to specific practices and rites within the religious community to live and practise the faith. The practice, in turn, strengthens the faith of the believers and anchors the religious values in their daily lives.

The institution of a religious community is the organisational structure that guides and regulates the beliefs and practices of its members. It establishes rules and norms that govern behaviour and interactions within the community. This institution can exercise legal and moral authority and thus influence the behaviour and beliefs of the faithful. In some religions, moral laws are considered to be revealed by the deity and, therefore, have supreme authority, guiding believers to conform to these ethical requirements.

The mutual influence of belief, practice and institution means that the members of a religious community are anchored in the community through their beliefs and actions. Belief sets the guidelines, practice consolidates this belief in everyday life, and the institution ensures that the rules and norms are followed. In this way, belief, practice and institution are closely linked in a religious community and shape the religious life of its members.

Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss, a French anthropologist and ethnologist whose work was fundamental to developing the theory of structuralism, viewed religion as part of a broader system of human thought and culture. While he did not clearly define religion, he analysed myths, which play a central role in many religions, as language systems that reflect the underlying structures of the human mind. For Lévi-Strauss, religion (and myth in particular) was a way for societies to organise and make sense of the world around them, revealing the universal structures of human thought. In his view, religion was also characterised by the human tendency to classify and organise experiences into binary opposites, such as life/death, good/evil, culture/nature, etc.

Hans Blumenberg

Hans Blumenberg, a German philosopher, took a different approach. His view of religion is closely interwoven with his understanding of human culture and the history of ideas. But he also saw religion as a fundamental human need for meaning, a way of coping with the “absolutism of reality” or the overwhelming nature of existence. For Blumenberg, religion offers stories, metaphors and symbols that enable people to navigate and make sense of their reality and prevent them from being overwhelmed by the sheer incomprehensibility and threat of the world. His view of religion focussed on how religion manifests itself in human life and culture rather than on structural or functional definitions.

Both scholars offered deep insights into the nature of religion, emphasising its role in human thought, culture and the existential search for meaning, albeit from very different angles. Lévi-Strauss’ structuralist approach focuses on the cognitive aspects of the way religion and myth structure human understanding. At the same time, Blumenberg emphasises the existential and phenomenological dimensions of religion as a response to human existence.

4 The Deep Psychological Consequences of Childhood Religious Trauma

Religious trauma in childhood is a condition that results from the difficulty of leaving an authoritarian, dogmatic religion. The induction of fear by religious institutions leads to a climate of fear and oppression that can have profound psychological consequences.

Especially the induction of fear as a deliberate means of controlling members, be it through physical punishment or the creation of fear of external threats or even the loss of group membership, leads to a climate of fear and oppression in the environment of religious institutions and groups.

People who leave such controlling religious communities experience confusion, poor critical thinking skills, negative beliefs about self-efficacy and self-worth, black-and-white thinking, perfectionism, difficulty in decision-making, depression, anxiety, anger, sadness, loneliness, difficulty with joy, loss of meaning, loss of social network, family breakdown, social awkwardness, sexual problems, and delays in developmental goals. In addition, those who have been the most sincere, devout, and committed may have the most difficulty when their world of religious faith collapses, which can lead to a fracturing of the self.

Authoritarian, isolationist and fear-based religious communities, in particular, can definitely contribute to religious trauma. Such communities paint a toxic picture of reality that favours authoritarianism and fear, leading to psychological damage. In particular, the teachings of hell, divine punishment, demons and a threatening “outside world” plant fear deep into the basic structure of the worldview of those affected.

Leaving such a controlling religious community is seen as a traumatic event, as these communities are the livelihood of their members and provide the only support against the perceived corrupt or hostile outside world, worldview, meaning, social and emotional satisfaction. The process of leaving such a community forces a complete rebuilding of reality, and this is done without the help and support of family and friends who remain in the religion.

In addition, a deep-rooted fear of terrible punishment for all sins and the problem of low self-esteem do not simply disappear overnight for survivors of religious trauma. On the contrary, they can grow into unbearable panic attacks. Ultimately, authoritarian religions teach the fear of the world and emphasise the necessity of belonging to a group for the salvation of the soul. After leaving the community, this favours lasting phobic or even paranoid thoughts and helplessness.

All religious beliefs and practices can cause harm or contribute to well-being. However, certain types of religion, particularly fundamentalist and patriarchal, have been found to convey both toxic teachings and toxic practices that can cause harm. Religious beliefs such as the doctrine of hell, divine punishment and eternal damnation can cause significant psychological stress. In addition, abuse, authoritarianism and the oppression of certain groups within religious institutions can lead to harm and trauma.

However, religious beliefs and practices can also contribute to well-being, especially when they promote values such as compassion, empathy and social support. Religion can give people comfort, meaning and direction in life, leading to an overall positive emotional and psychological state.

5 Child development, trauma and religious practices

The link between religious trauma and childhood trauma lies in the fact that children lack the resilience and intellectual resources to distance themselves from harmful religious experiences and, therefore, internalise them into their emerging worldview. Children who grow up in authoritarian religious environments become victims of indoctrination, abuse and emotional manipulation, resulting in long-term psychological damage.

RTS develops as a reaction to prolonged abuse by a controlling religious community. Through indoctrination, children learn out of fear to suppress their natural spontaneity and independent thinking and to mistrust their own feelings and instead follow external authorities, scriptures and religious leaders unquestioningly.

In addition, children are traumatised by religious ideas of hell, punishment and the constant feeling of being threatened by an all-powerful God, which can lead to a condition similar to Complex PTSD.

Regardless of an authoritarian religious environment, ideas of hell, punishment, and an all-powerful avenging God harm children’s mental health. They cause intense anxiety, toxic shame and a deeply ingrained sense of guilt. The idea of an almighty and punishing deity deciding people’s fate causes powerlessness and helplessness, which in turn increases stress and anxiety.

The idea of hell as a place of eternal damnation awakens children’s fears of death and damages their self-esteem. A constant fear of punishment and the wrath of God leads to unbearable psychological pressure and inner tensions that cannot remain without consequences for children’s mental health.

Children in authoritarian religious environments are also under relentless pressure to conform to religious norms and rules, as obedience and punishment play a central role. Given children’s inevitable experience of their own ineptitude and inadequacy, such relentless demands create feelings of fear of making mistakes and deviating from the rules, of worthlessness and of being at the mercy of others.

The complex link between religion and childhood trauma illustrates how profoundly religious experiences in childhood affect psychological well-being. Children are biologically dependent on trusting their adult caregivers to survive. Religious practices inhibit children’s normal cognitive, social, emotional and moral development. The intersection of authoritarian religious teachings and children’s biological need to trust authority also contributes to the invisibility of children’s suffering and lifelong pressure from family and religious community.

Overall, religious institutions and doctrines contribute, even indirectly and unintentionally, to childhood trauma by creating an environment that can cause anxiety, guilt and inferiority complexes, as well as fostering authoritarian control and abuse that can affect children’s emotional well-being.

It must also be mentioned that abuse, whether physical, sexual or emotional, can occur and has repeatedly occurred in religious families and faith communities without corresponding authoritarian structures intervening. Given the damaged physical and emotional development of affected children, this must lead to particularly severe trauma, as such perpetrators build up an inescapable, isolating, threat-based model of reality to intimidate their victims.

6 Highlighting the Importance of Understanding and Addressing Religious Trauma from Early Years

The discussion around the topic of childhood religious trauma has led us into a complex field of psychological, social and spiritual dimensions, showing that the role of religion in human life can be both beneficial and harmful. The concept of religious trauma (RTS) sheds light on understanding and recognising the profound impact of authoritarian and dogmatic religious practices on individual psychological well-being, particularly in children.

Understanding religion as a multidimensional phenomenon, encompassing belief, practice and institutional structures, is crucial to recognising the mechanisms through which religious experiences can be traumatising. While belief and practice concern personal and collective spiritual dimensions, the institutional aspects of religion often shape how belief and practice are organised and enforced in society. These structures can be both supportive and oppressive and have the potential to have both positive and negative psychological effects on their members, especially children.

Children who grow up in highly authoritarian religious environments are particularly vulnerable to religious trauma as they internalise the dogmatic teachings and associated fears and guilt without the opportunity to question or resist them critically. That can lead to long-term psychological problems, including anxiety, depression, low self-esteem and difficulties in developing a healthy self-image and social interaction.

The works of Claude Lévi-Strauss and Hans Blumenberg provide critical theoretical frameworks for understanding the profound role of religion in human culture and psychology. While Lévi-Strauss emphasises the structural aspects of myth and religion, Blumenberg emphasises religion’s existential and phenomenological significance as a response to the human condition. Both perspectives offer valuable insights into how religious beliefs and practices shape human consciousness and how they can become a source of comfort and meaning as well as trauma and suffering.

In summary, understanding and recognising religious trauma are essential steps in addressing the psychological impact of authoritarian religious practices on children. By examining the various dimensions of religion and its effects on individual and collective well-being, we can find ways to promote the healing aspects of religion while challenging and reforming the potentially harmful practices and structures. Providing resources and support to those affected by religious trauma is an essential step in facilitating healing and recovery and developing a deeper understanding of the complex role of religion in human life.

The finding that the primary source of support available to those affected by religious trauma is testimonials, while structured support services and resources are scarce, highlights the need to increase awareness and the availability of specialised support services. The power of personal stories lies in their ability to break through the feeling of isolation and show those affected that they are not alone. However, these accounts alone are often not enough to begin the journey of healing and processing.

A systematic approach is needed to help those affected effectively. It includes professional therapeutic services that specifically address the issue of religious trauma, support groups dedicated to this issue, and informational and educational materials that provide information about the nature and impact of religious trauma. The development and dissemination of such resources can help support and accelerate the healing process for individuals struggling with the effects of religious trauma.

Literature:

Boddice, Rob. 2019. A History of Feelings. London: Reaktion Books.

Chomsky, Noam. 2011. How the World Works (Real Story (Soft Skull Press)) (English Edition) Kindle Ausgabe. Soft Skull.

Eliade, Mircea. 1954. Cosmos and History: The Myth of the Eternal Return. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Eliade, Mircea. 1964. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Penguin Books.

Eliade, Mircea. 1978. History of Religious Ideas, Volume 1: From the Stone Age to the Eleusinian Mysteries. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Eliade, Mircea. 1982. History of Religious Ideas, Volume 2: From Gautama Buddha to the Triumph of Christianity. University of Chicago Press.

Eliade, Mircea. 1988. History of Religious Ideas, Volume 3: From Muhammad to the Age of Reforms. University of Chicago Press.

Finch, Jamie Lee. 2019. You Are Your Own: A Reckoning With the Religious Trauma of Evangelical Christianity. Independently Published.

Foucault, Michel. 1978. Dispositive Der Macht: Über Sexualität, Wissen Und Wahrheit. Merve.

Franz, Marie-Louise von. 2001. Psychotherapy. Shambhala.

Han, Byung-Chul. 2014. Psychopolitik: Neoliberalismus Und Die Neuen Machttechniken. Kindle Ausgabe. S. Fischer Verlag.

Iagher, Matei. 2018. “Beyond Consciousness: Psychology and Religious Experience in the Early Work of Mircea Eliade (1925-1932).” New Europe College Stefan Odobleja Program Yearbook (2017+ 18): 119–48.

Klein, Melanie. 1984. Love, Guilt, and Reparation, and Other Works, 1921-1945. New York: The Free Press.

Maxwell, Paul. 2022. The Trauma of Doctrine: New Calvinism, Religious Abuse, and the Experience of God. Lanham • Boulder • New York • London: Fortress Academic.

Moellendorf, Darrel. 2019. “Hope for Material Progress in the Age of the Anthropocene.” In The Moral Psychology of Hope, edited by Claudia Blöser, and Titus Stahl, 249–64. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Nussbaum, Martha C. 2012. The New Religious Intolerance. Overcoming the Politics of Fear in an Anxious Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

O’Gieblyn, Meghan. 2021. God, Human, Animal, Machine: Technology, Metaphor, and the Search for Meaning. Anchor.

Petersen, Brooke N. 2022. Religious Trauma: Queer Stories in Estrangement and Return. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Peterson, Jordan B. 2002. Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief (English Edition) Kindle Ausgabe. New York – London: Routledge.

Price, Max D. 2021. Evolution of a Taboo: Pigs and People in the Ancient Near East. New York: Oxford University Press, USA.

Rafaeli, Eshkol, Jeffrey E. Young, and David P. Bernstein. 2013. Schematherapie. Junfermann Verlag GmbH.

Roediger, Eckhard. 2016. Schematherapie: Grundlagen, Modell Und Praxis. Stuttgart: Schattauer.

Russell, Bertrand, and Simon Blackburn. 2004. Why I Am Not a Christian: And Other Essays on Religion and Related Subjects. Psychology Press.

Sagan, Carl. 1997. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark.

Scholem, Gershom. 1997. On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism. New York: Schocken.

Stein, Alexandra. 2016. Terror, Love and Brainwashing: Attachment in Cults and Totalitarian Systems. Taylor & Francis.

Tangney, June P. 2002. “Perfectionism and the Self-Conscious Emotions: Shame, Guilt, Embarrassment, and Pride.” In Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment, 199–215. Washington: American Psychological Association.